According to an IMF's recently unveiled report by Mehdi Benatiya Andaloussi, Nina Biljanovska, Alessia De Stefani and Rui Mano in countries where the housing channels are strong, monitoring housing market developments and changes in household debt service can help identify early signs of overtightening. Where monetary policy transmission is weak, more forceful early action can be taken when signs of overheating and inflationary pressures first emerge.

Central banks have raised interest rates significantly over the past two years to combat post-pandemic inflation. Many thought this would lead to a slowdown in economic activity. Yet, global growth has held broadly steady, with deceleration only materializing in some countries.

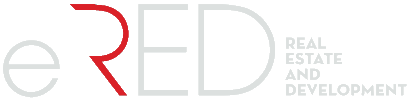

Monetary policy has greater effects in countries where the share of fixed-rate mortgages is low

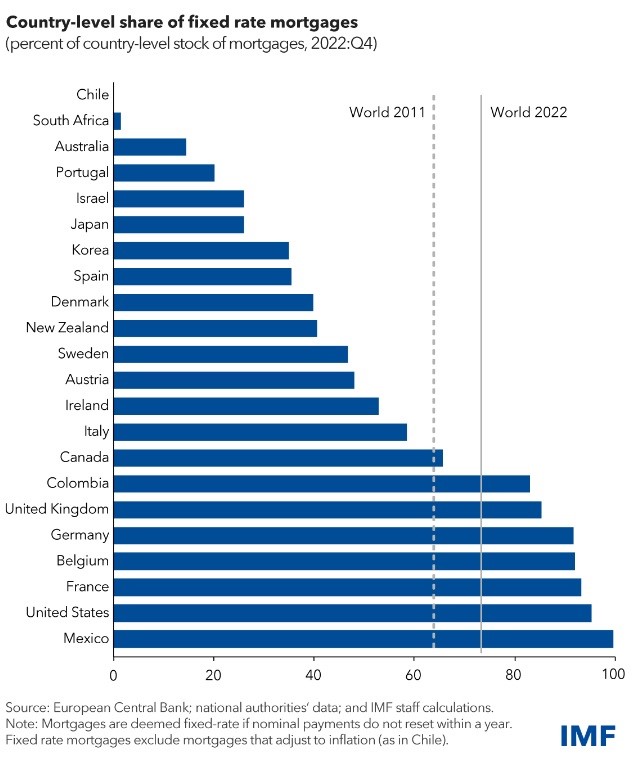

Monetary policy has greater effects on activity in countries where the share of fixed-rate mortgages is low. This is due to homeowners seeing their monthly payments rise with monetary policy rates if their mortgage rates adjust. By contrast, households with fixed-rate mortgages will not see any immediate difference in their monthly payments when policy rates change.

The effects of monetary policy are also stronger in countries where mortgages are larger compared to home values, and in countries where household debt is high as a share of GDP. In such settings, more households will be exposed to changes in mortgage rates, and the effects will be stronger if their debt is higher relative to their assets.

Housing market characteristics also matter

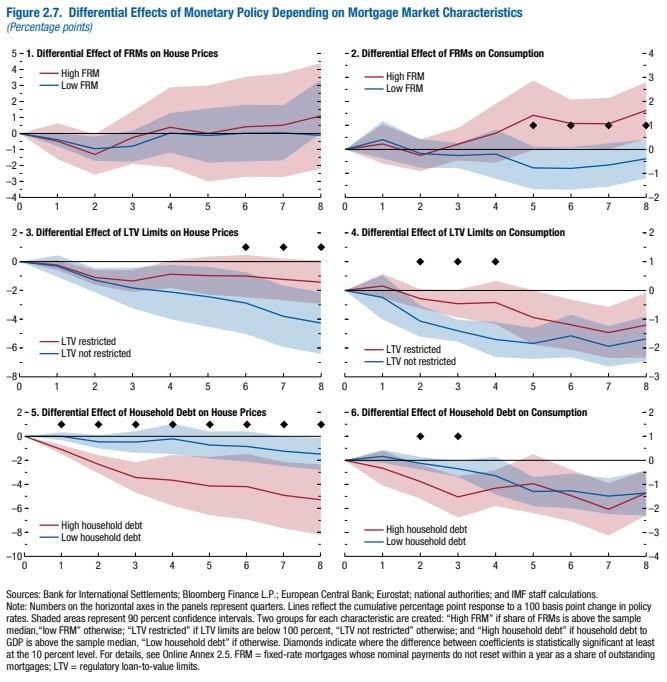

The transmission of monetary policy is stronger where housing supply is more restricted. For example, lower rates will decrease borrowing costs for first-time home buyers and increase demand. Where supply is restricted, this will lead to home price appreciation. Existing owners will see their wealth increase as a result, leading them to consume more, including if they can use their home as collateral to borrow more.

The same holds true where home prices have recently been overvalued. Sharp price increases are often driven by overly optimistic views about future house prices. These are typically accompanied by excessive leverage, prompting spirals of falling home prices and foreclosures when monetary policy tightens, which can lead to starker income and consumption declines.

Mortgage and real estate markets have undergone several shifts since the global financial crisis and the pandemic.

At the beginning of the recent hiking cycle and after a long period of low interest rates, mortgage interest payments were historically low, the average maturity was long, and the average share of fixed-rate mortgages was high in many countries. In addition, the pandemic led to population shifts away from city centers and to relatively less-supply-constrained areas.

As a result, the housing channels of monetary policy may have weakened, or at least been delayed, in several countries.

Leaving rates higher for longer, could nevertheless be a greater risk now

Most central banks have made significant progress toward their inflation target. It could follow from the discussion that, if transmission is weak, erring on the side of too much tightening is always less costly. However, overtightening, or leaving rates higher for longer, could nevertheless be a greater risk now.

While fixed-rate mortgages have indeed become more common in many countries, fixation periods are often short. Over time, and as rates on these mortgages reset, monetary policy transmission could suddenly become more effective and so depress consumption, especially where households are heavily indebted.

The longer time rates are kept high, the greater the likelihood that households will feel the pinch, even where they have so far been relatively sheltered.