Thanks to urbanization, this means property prices should rise significantly in the long run—more or less summing up the common narrative on the value growth of urban homes. The strong real estate boom of the last decade underlines this credo once again, the UBS notes in its recently unveiled UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index 2022.

However, if urban residential rents are used as a benchmark, the supposed scarcity effect evaporates: rents have only risen hand in hand with local wages over the same period.

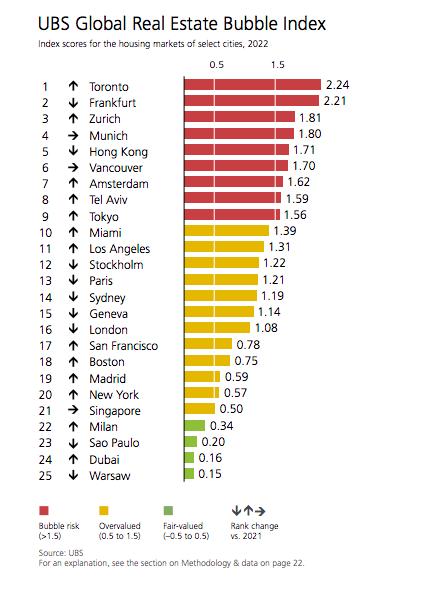

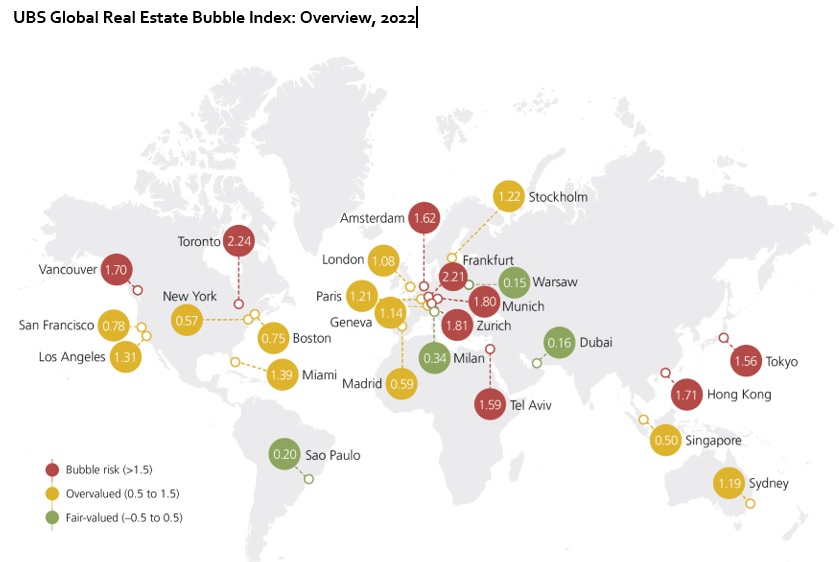

Nominal house price growth in the 25 cities analyzed accelerated to almost 10% on average from mid-2021 to mid-2022, the highest increase since 2007. In fact, all but three cities—Paris, Hong Kong, and Stockholm—saw their house prices climb. The highest regional price growth of more than 15% in nominal terms was recorded in the North American cities.

On top of this, an acceleration in the growth of outstanding mortgages was evident in virtually all cities, and for the second year in a row, household debt grew significantly faster than the long-term average. The lending boom was conspicuously strong in the Middle East, the US, Canada, and Australia.

Since the pandemic we observe an increase in aggregate household debt relative to economic output in many of the analyzed economies. Even though current valuations are elevated, index scores have not increased on average compared to last year.

Strong income and rental growth have mitigated the imbalances. Housing prices in nonurban areas have increased faster than in cities for the second consecutive year. Additionally, price growth has slowed significantly in inflation-adjusted terms. House price growth was outpaced by consumer prices in 10 out of 25 markets analyzed.

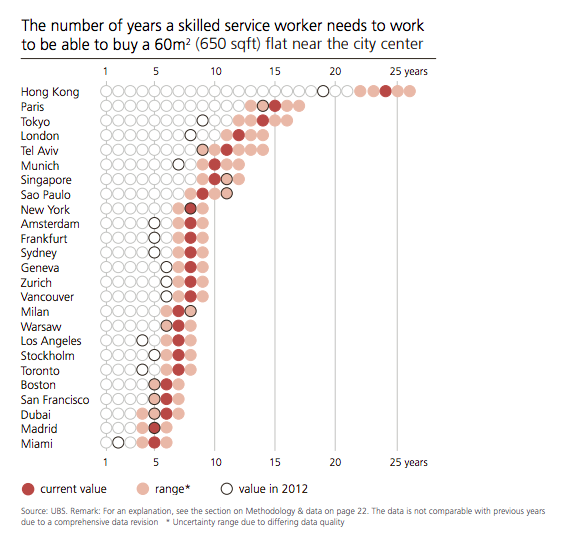

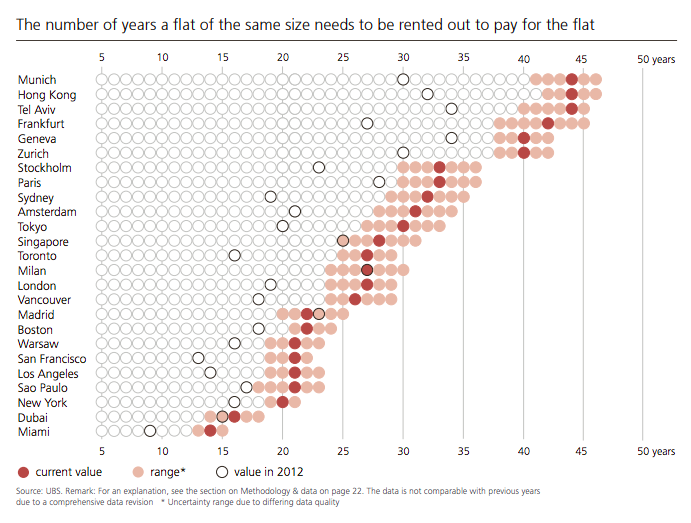

Buying a 60 sqm apartment exceeds the budget of those who earn the average annual income in the skilled service sector in most world cities.

In Hong Kong, even those who earn twice that income would struggle to afford an apartment of that size. House prices have also decoupled from local incomes in Paris, Tokyo, London, and Tel Aviv, where price-to-income multiples exceed 10 by far.

Unaffordable housing is often a sign of strong foreign investment demand, tight zoning, and strict rental market regulations. If investment demand weakens, the risk of a price correction increases and prospects for long-term appreciation shrink.

By contrast, housing is relatively affordable in Miami, Madrid, Dubai, San Francisco, and Boston, which limits the risk of a price correction in those cities.

Given relatively high incomes, purchasing a 60 square meter apartment is also relatively feasible for residents of Los Angeles, Milan, Geneva, or Zurich. For homebuyers, affordability also depends on mortgage rates and amortization obligations. If interest and amortization rates are relatively high, the burden on monthly income can be heavy even in cities with low price-to-income multiples like in the US. Conversely, elevated purchase prices can be sustained with low interest rates and no requirement of full amortization, as seen in regions like Switzerland and the Netherlands.

Identifying a bubble

Price bubbles are a recurring phenomenon in property markets. The term “bubble” refers to a substantial and sustained mispricing of an asset, the existence of which cannot be proved unless it bursts. But historical data reveals patterns of property market excesses.

Typical signs include a decoupling of prices from local incomes and rents, and imbalances in the real economy, such as excessive lending and construction activity. The UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index gauges the risk of a property bubble on the basis of such patterns. The index does not predict whether and when a correction will set in. A change in macroeconomic momentum, a shift in investor sentiment or a major supply increase could trigger a decline in house prices.

What is the status of Eurozone cities

Frankfurt and Munich exhibit the biggest risks of a property bubble among the Eurozone markets covered in this report . Both German cities have seen property prices more than double in nominal terms over the last decade, though growth has cooled to around 5% between mid-2021 and mid-2022 from double-digit levels. In Munich, the housing market is supported by an ultra-low vacancy rate and a growing work force, but the rather subdued German economic outlook presents a drag on housing demand.

Higher mortgage rates have already worsened affordability: a skilled worker from the service sector can now buy an apartment with one room less in Munich on average than before the pandemic. Amsterdam’s housing market saw the strongest price growth among Eurozone cities analyzed at 17% between mid-2021 and mid-2022 in nominal terms.

This comes as nominal property prices have doubled within the last ten years. Demand has seen less of a drag from the recent rise in mortgage rates, which have increased by less than in other Eurozone countries. Overall, bubble risk has increased only marginally as well, with the city’s price growth roughly in line with the national average. Moreover, nominal rents and incomes have also climbed, although not at the same pace as property prices.

In Madrid, property price growth has accelerated since the onset of the pandemic. The Spanish capital is now in overvalued territory, though a skilled service worker can still buy the most living space there among all Eurozone markets in the study.

Alongside the post-pandemic economic recovery and lower interest rates, fiscal incentives to renovate buildings have also supported price growth in Milan after a decade of stagnating prices. Continuation of these incentives, the nearly completed extension of the underground railway, and the Olympic games in 2026 all contribute to sustaining valuations in the medium term.

Housing in Paris is an outlier among the Eurozone markets covered. Nominal property prices stagnated between mid2021 and mid-2022 and significantly trailed the country average. Rents were flat over the same period and incomes recovered slightly.

This has pushed the French capital out of the bubble risk zone, though the housing market can still be considered overvalued. Paris remains the least affordable Eurozone market in the study.

London’s housing market is in overvalued territory. Prices are now 6% higher than a year ago, supported by a structural shortage of housing amid increasing post-pandemic demand. But the index score has remained stable over the last quarters.

Rents have surged as would-be buyers face difficulties finding appropriate properties. Moreover, housing prices in the city still lag the nationwide average.

Since 2018, housing prices in Warsaw have climbed by 10% annually driven by unprecedented excess demand. The city has had one of the strongest job markets in Eastern Europe, with the boom luring new citizens and buy-to-let investors. The market is still fair-valued at this stage, but housing has become increasingly unaffordable given the high prices and rapidly rising mortgage rates. And as consumer prices surge, purchasing

property loses its priority for many. This should put some pressure on future price increases.